Service Strategy

2. Service Management as a Practice

2.1 What Is Service Management?

Service management is a set of specialized organizational capabilities for providing value to customers in the form of services. The capabilities take the form of functions and processes for managing services over a lifecycle, with specializations in strategy, design, transition, operation, and continual improvement. The capabilities represent a service organization's capacity, competency, and confidence for action. The act of transforming resources into valuable services is at the core of service management. Without these capabilities, a service organization is merely a bundle of resources that by itself has relatively low intrinsic value for customers.

Service management

Service management is a set of specialized organizational capabilities for providing value to customers in the form of services.

|

Service management capabilities are influenced by the following challenges that distinguish services from other systems of value creation such as manufacturing, mining and agriculture:

- Intangible nature of the output and intermediate products of service processes: difficult to measure, control, and validate (or prove).

- Demand is tightly coupled with customer's assets: users and other customer assets such as processes, applications, documents and transactions arrive with demand and stimulate service production.

- High-level of contact for producers and consumers of services: little or no buffer between the customer, the front-office and back-office.

- The perishable nature of service output and service capacity: there is value for the customer in receiving assurance that the service will continue to be supplied with consistent quality. Providers need to secure a steady supply of demand from customers.

Case study

Organizational capabilities are shaped by the challenges they are expected to overcome. An example of this is how in the 1950s Toyota developed unique capabilities to overcome the challenge of smaller scale and financial capital compared to its American rivals. Toyota developed new capabilities in production engineering, operations management and supply-chain management to compensate for limits on the size of inventories it could afford, the number of components it could make on its own, or being able to own the companies that produced them. The need for financial austerity, tight coordination, and greater dependency on suppliers led to the development of the most copied production system in the world.

|

|

| Figure 2.1 Generalized Patterns and specialized instances |

|

|

The characteristics described above are not universal constraints.' Innovative business models and technological innovation have relaxed the constraining effects of these characteristics. What matters is the need to recognize these characteristics when they do appear, and identify them as challenges in service management.

Service management is also a professional practice supported by an extensive body of knowledge, experience, and skills. A global community of individuals and organizations in the public and private sectors fosters its growth and maturity. Formal schemes that exist for the education, training and certification of practising organizations and individuals influence its quality. Industry best practices, academic research and formal standards contribute to its intellectual capital and draw from it.

The origins of service management are in traditional service businesses such as airlines, banks, hotels and telephone companies. Its practice has grown with the adoption by IT organizations of a service-oriented approach to managing IT applications, infrastructure and processes. Solutions to business problems and support for business models, strategies and operations are increasingly in the form of services. The popularity of shared services and outsourcing has contributed to the increase in the number of organizations who are service providers, including internal organizational units. This in turn has strengthened the practice of service management, at the same time imposing greater challenges on it. |

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

2.2 What Are Services?

2.2.1 The Value Proposition

Service

A service is a means of delivering value to customers by facilitating outcomes customers want to achieve without the ownership of specific costs and risks.

|

Services are a means of delivering value to customers by facilitating outcomes customers want to achieve without the ownership of specific costs and risks. Outcomes are possible from the performance of tasks and are limited by the presence of certain constraints. Broadly speaking, services facilitate outcomes by enhancing the performance and by reducing the grip of constraints. The result is an increase in the possibility of desired outcomes. While some services enhance performance of tasks, others have a more direct impact. They perform the task itself.

The preceding paragraph is not just a definition, as it is

a recurring pattern found in a wide range of services. Patterns are useful for managing complexity, costs, flexibility and variety. They are generic structures useful to make an idea work in a wide range of environments and situations. In each instance the pattern is applied with variations that make the idea effective, economical, or simply useful in that particular case.

Take, for example, the generalized pattern of a storage system. Storage is useful for holding, organizing or securing assets within the context of some activity, task or performance. Storage also creates useful conditions such as ease of access, efficient organization or security from threats. This simple pattern is inherent in many types of storage services, each specialized to support a particular type of outcome for customers (Figure 2.1).

For various reasons, customers seek outcomes but do not wish to have accountability or ownership of all the associated costs and risks. For example, a business unit needs a terabyte of secure storage to support its online shopping system. From a strategic perspective, it wants the staff, equipment, facilities and infrastructure for a terabyte of storage to remain within its span of control. It does not want, however, to be accountable for all the associated costs and risks, real or nominal, actual or perceived. Fortunately, there is a group within the business with specialized knowledge and experience in

large-scale storage systems, and the confidence to control the associated costs and risks. The business unit agrees to pay for the storage service provided by the group under specific terms and conditions.

The business unit remains responsible for the fulfillment

of online purchase orders. It is not responsible for the operation and maintenance of fault-tolerant configurations of storage devices, dedicated and redundant power supplies, qualified personnel, or the security of the building perimeter, administrative expenses, insurance, compliance with safety regulations, contingency measures, or the optimization problem of idle capacity for unexpected surges in demand. The design complexity, operational uncertainties, and technical trade-offs associated with maintaining reliable high-performance storage systems lead to costs and risks the business unit is simply not willing to own. The service provider assumes ownership and allocates those costs and risks to every unit of storage utilized by the business and any other customers of the storage service.

2.2.2 Value Composition

From the customer's perspective, value consists of two primary elements: utility or fitness for purpose and warranty or fitness for use.

- Utility is perceived by the customer from the attributes of the service that have a positive effect on the performance of tasks associated with desired outcomes. Removal or relaxation of constraints on performance is also perceived as a positive effect.

- Warranty is derived from the positive effect being available when needed, in sufficient capacity or

service management as a practice magnitude, and dependably in terms of continuity and security

Utility is what the customer gets, and warranty is how it is delivered.

Customers cannot benefit from something that is fit for purpose but not fit for use, and vice versa. It is useful to separate the logic of utility from the logic of warranty for the purpose of design, development and improvement (Figure 2.2). Considering all the separate controllable inputs allows for a wider range of solutions to the problem of creating, maintaining and increasing value.

Take the case of the business unit utilizing the highperformance online storage service. For them the value is not just from the functionality of online storage but also from easy access to no less than one terabyte of faulttolerant storage, as and when needed, with confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data. Chapter 3 of Service Strategy provides further detail on the concepts of utility and warranty.

An outcome-based definition of service moves IT organizations beyond Business-IT alignment towards Business-IT integration. Internal dialogue and discussion on the meaning of services is an elementary step towards alignment and integration with a customer's business (Figure 2.3). Customer outcomes become the ultimate concern of Product Managers instead of the gathering of requirements, which is necessary but not sufficient. Requirements are generated for internal coordination and control only after customer outcomes are well understood. Chapter 4 of Service Strategy provides detail on the practical use of outcome-based definitions.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

2.3 The Business Process

|

| Figure 2.3 A conversation about the definition and meaning of service |

|

| Figure 2.4 Business processes apply experience, know-how and resources |

| Business outcomes are produced by business processes governed by objectives, policies and constraints. The processes are supported by resources including people, knowledge, applications and infrastructure. Workflow coordinates the execution of tasks and flow of control between resources, and intervening action to ensure adequate performance and desired outcomes. Business processes are particularly important from a service management perspective. They apply the organization's cumulative knowledge and experience to the achievement of a particular outcome (Figure 2.4).

Processes are strategic assets when they create competitive advantage and market differentiation. As a result, business processes define many of the challenges faced by service management. The nature and dynamics of the relationship between business processes and IT best explains this.

|

The workflow of business processes is a factor of business productivity. Business processes can span organizational and geographic boundaries, often in complex variants creating unique designs and patterns of execution (Figure 2.5). As the importance of business process has emerged, businesses have realized they must consider not only internal practices, but also their interactions with suppliers and customers. These fundamental needs form the basic motivation for the management of business processes as valuable assets.

|

| Figure 2.5 The end points of a business process are often defined by enterprise applications |

Business managers demand IT systems that make processes more transparent, dynamically serving and expediting business process flows. End-to-end business processes have come to depend on distributed systems. Business managers challenge IT organizations to engage with them at the level of business processes. They want assurance that applications and infrastructure will support new business initiatives. However, there are coordination and cooperation problems between the two sides. Business managers may not understand the complexity and detail of creating the business process within the realm of information, applications, and infrastructure. IT managers may not have a clear understanding of exactly what business managers are trying to accomplish. The problem gets worse with complexity, duplication, and the absence of clear models for coordination and control. The following section shows how the principles of service

management are useful in solving many of these problems between the business and IT.

Process

A process is a set of coordinated activities combining and implementing resources and capabilities in order to produce an outcome, which, directly or indirectly, creates value for an external customer or stakeholder.

|

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

2.4 Principles Of Service Management

Service management has a set of principles to be used for analysis, inference, and action in various situations involving services. These principles complement the functions and processes described elsewhere in the ITIL Core Library. When functions and processes are to be changed, these principles provide the necessary guidance and reference. When solving problems related to services, these principles are to be used to resolve ambiguity and conflict.

|

| Figure 2.6 Relationships defined by the dynamics of ownership, control and utilization |

2.4.1 Specialization and Coordination

The aim of service management is to make available capabilities and resources useful to the customer in the highly usable form of services at acceptable levels of quality, cost, and risks. Service providers help relax the constraints on customers of ownership and control of specific resources. In addition to the value from utilizing such resources now offered as services, customers are freed to focus on what they consider to be their core competence. The relationship between customers and service providers varies by specialization in ownership and control of resources and the coordination of dependencies between different pools of resources (Figure 2.6).

Customers specialize in business management to achieve one set of outcomes using a set of resources (Pool A). Similarly, service providers specialize in service management with another set (Pool B). Service management coordinates the dependencies between the two sides through assurances and utilization. Customers are content with utilization of certain resources (Pool B) unless ownership is a prerequisite for strategic advantage.

Specialization is a necessary condition for developing organizational capabilities. Management potential accumulates from specialized knowledge and experience with a set of resources." Specialization drives the grouping of capabilities and resources under the same span of control to achieve focus, expertise, and excellence. Coordination of capabilities and resources is easier when they are under the same span of control because of accountability, authority

and managerial attention. Capabilities and resources with high degree of dependency and interaction are grouped together to reduce the need for coordination." Where coordination is easy through well-defined interfaces, protocols and agreements, they are placed under the control of the group most capable of managing them." The strength of specialized capabilities on one side relative to the other creates the difference in potential, which justifies the transfer of resources from Pool A to Pool B and makes the case for a new or changed service.

It is important to note in this context that scale and scope of the customer and service provider organizations vary, from large enterprises to small businesses, autonomous business units and sub-divisions to small internal groups and teams who provide services. The principles remain the same. What may change are the values of variables such as the transaction costs, strategic industry factors, economies of scale and regulatory environments.

Transaction costs, the nature of resources to manage, the feasibility of encapsulating them into services, and confidence in service management drive decisions on specialization and coordination. While outsourcing is a noticeable trend, there are many instances of customers deciding to retain certain capabilities in-house or even bring them back in.

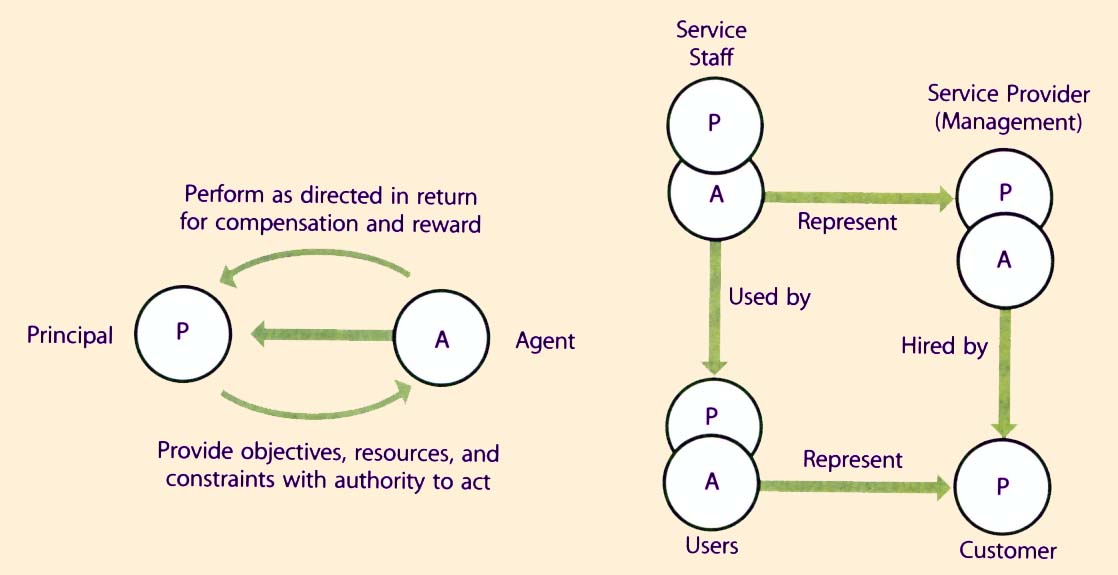

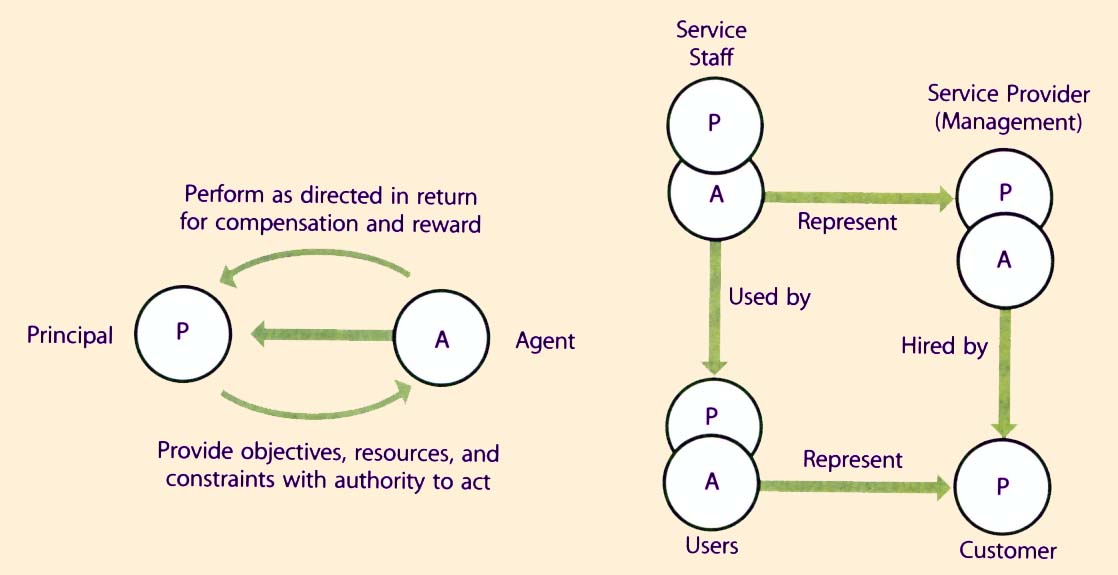

2.4.2 The Agency Principle

Principals employ or hire agents to act on their behalf towards some specific objectives. Agents may be employees, consultants, advisors or service providers. Agents act on behalf of principals who provide objectives, resources (or funds), and constraints for agents to act on. They provide adequate sponsorship and support for agents to succeed on their behalf. Agents act in the interest of their principals, for which they receive compensation and reward, and in their own self-interest (Figure 2.7). Written or implied contracts record this agreement between principals and agents. Employment contracts, service agreements and performance incentive plans are examples.

Within the context of service management, customers are principals who have two types of agents working for them - service providers contracted to provide services, and users of those services employed by the customer. Users need not be on the payroll of the customer. Service agents act as intermediary agents who facilitate the exchange between service providers and customers in conjunction with users. Service agents are typically the employees of the service provider but they can also be systems and processes that users interact with in self-service situations. Value for customers is created and delivered through these interlocking relationships between principals and agents. The agency model is also applied in client/server models widely used in software design and enterprise architecture. Software agents interact with users on behalf of back-end functions, processes, and systems to which they provide access.

|

|

| Figure 2.7 The agency model in service management |

|

2.4.3 Encapsulation

Customers care about affordable and reliable access to the utility of assets. They are not concerned with structural complexity, technical details, or low-level operations. They prefer simple and secure interfaces to complex configurations of resources such as applications, data, facilities, and infrastructure. Encapsulation hides what is not the customer's concern and exposes as a service what is useful and usable to them. Customers are concerned only with utilization.

Encapsulation follows three separate but closely related principles: separation of concerns, modularity, and loose coupling.

2.4.3.1 Separation Of Concerns

Complex issues or problems can be resolved or separated into distinct parts or concerns. Specialized capabilities and resources address each concern leading to better outcomes overall. This improves focus and allows optimization of systems and processes at a manageable scale and scope. Challenges and opportunities are suited with appropriate knowledge, skills, and experience.

It is necessary to identify persistent and recurring patterns, to separate fixed elements from those that vary, and to distinguish what from how (Figure 2.1). These separations are important for a service-oriented approach to IT management or simply service orientation. For example, it is useful to identify and consolidate demand with common characteristics but different sources and serve it with shared services.

2.4.3.2 Modularity

Modularity is a structural principle used to manage complexity in a system .12 Functionally similar items are grouped together to form modules that are self-contained and viable. The functionality is available to other systems or modules through interfaces. Modularity contributes to efficiency and economy by reducing duplication, complexity, administrative overheads, and the cost of changes. It has a similar impact through the reuse of modules.

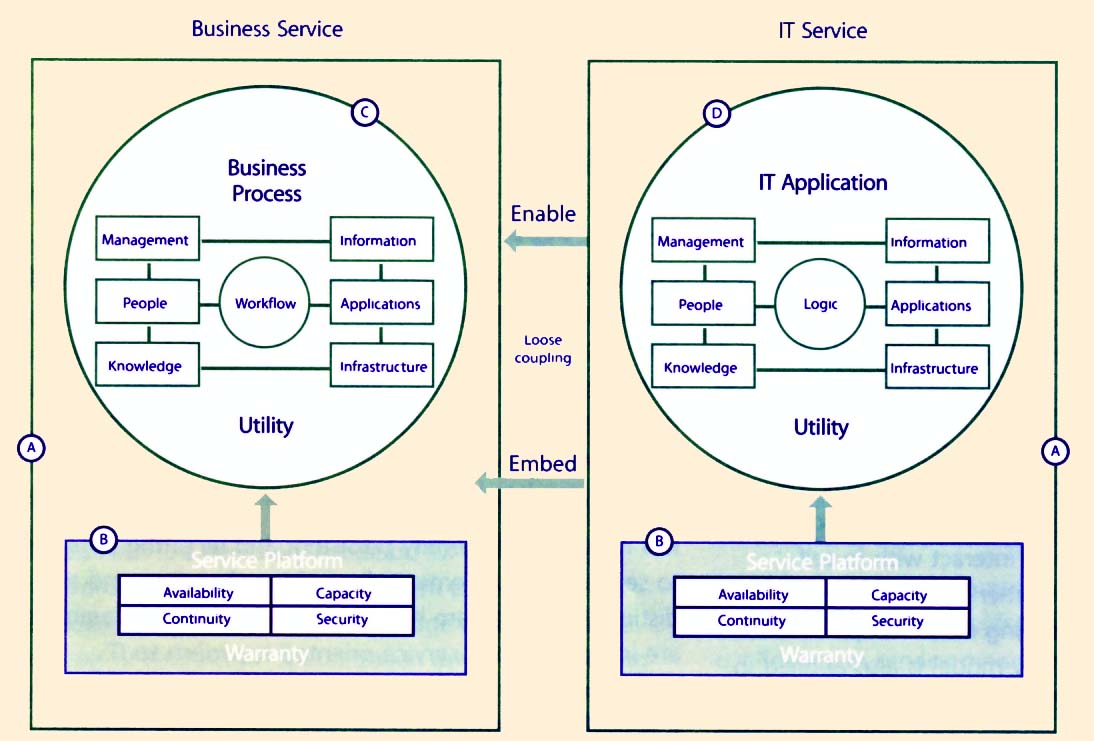

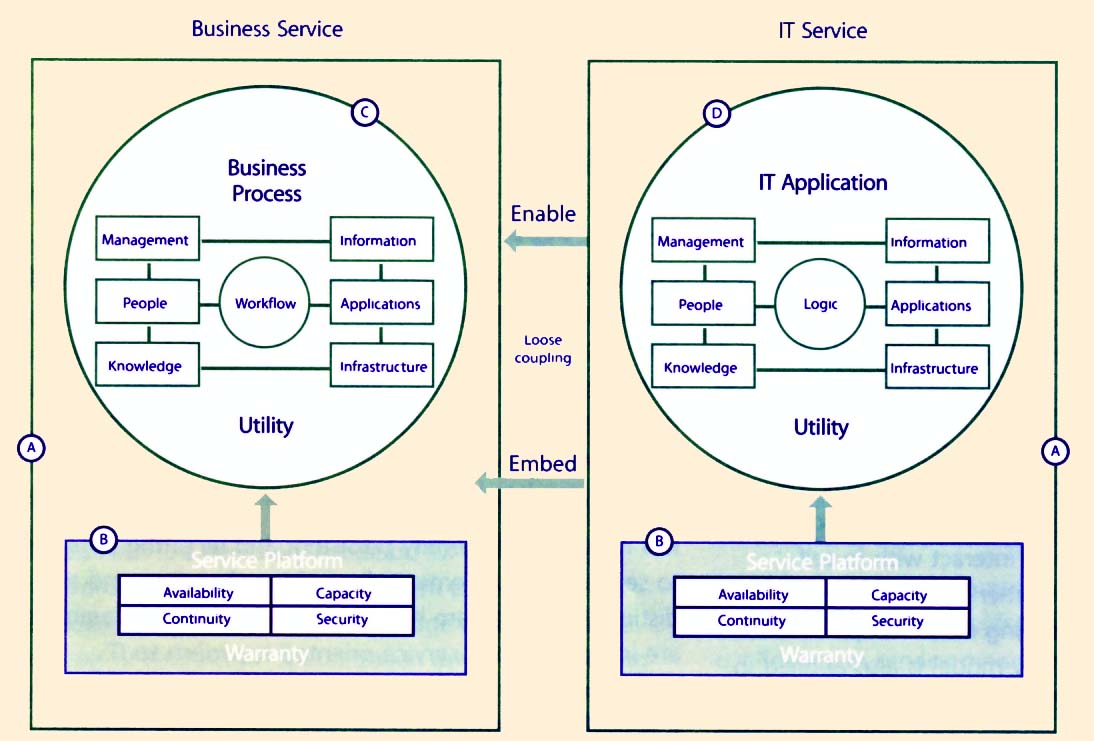

Encapsulation is possible at several levels of granularity, from software and hardware components to business processes and organizational design. Figure 2.8 illustrates the role of service management in encapsulating business processes and IT applications into business services and IT Services.

2.4.3.3 Loose Coupling

Separation of concerns and modularity facilitate loose coupling between resources and their users. With loose coupling, it is easier to make changes internal to the resource without adversely affecting utilization. It also avoids forcing changes on the customer's side, which can add unexpected costs to the customer. Loose coupling also allows the same set of resources to be dynamically assigned to different uses. This has several advantages, including shared services, Demand Management, redundancy, and investment protection for the customer

and the service provider from reduced lock-in. Loose coupling requires good design, particularly of service interfaces, without which there will be more problems than benefits.

2.4.4 Principles of Systems

System

A system is a group of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent components that form a unified whole, operating together for a common purpose.

|

2.4.4.1 Open-loop And Closed-loop Control Processes

There are two types of control processes: open-loop and closed-loop. Control processes in which the value of the outcome has no influence on the process input are openloop. Control processes in which the value of the outcome has influence (with or without some delay) on the process input in such a manner as to maintain the desired value are closed-loop. Open-loop systems take controlling action based simply on inputs. Changes in inputs result in changes in action. Effectiveness of open-loop systems depends excessively on foresight in design of all possible conditions associated with outcomes. When there are exceptions, open-loop systems are unable to cope. Control action in closed loop systems is goal driven and sensitive to disturbances or deviations.

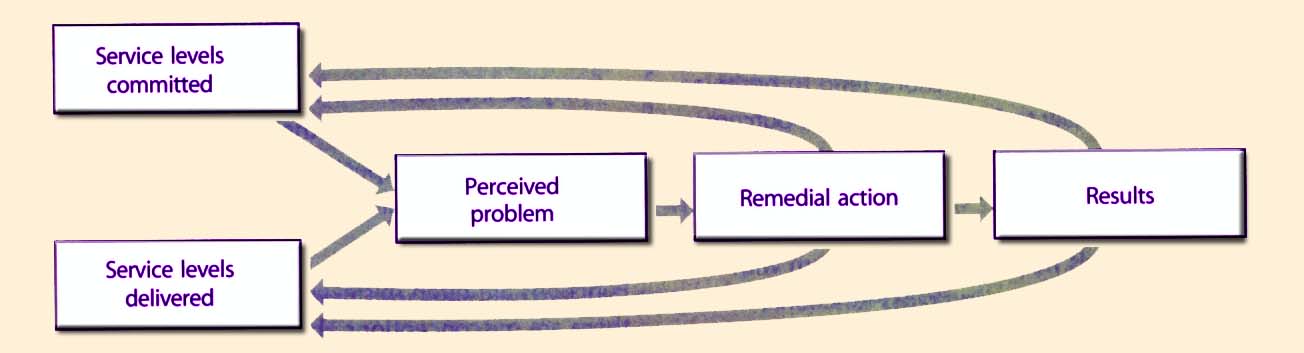

| | Figure 2.7 The agency model in service management |

|

- Package business processes and IT applications into service

- Provide service interface and ensure that service is available for utilization with adequate capacity, continuity and security.

- Improve business process to increase the utility of business services.

- Improve IT applications to increase the utility of IT services.

- Service management with ITIL for a and b.

Process improvement with Six Sigma for c.

Application development and maintenance with CMMI for d.

|

Open-loop solutions attempt to solve the problem by good design, to make sure it does not occur in the first place. Once a design is implemented, mid-course corrections are not made. Closed-loop solutions, however are based on compensating feedback. A well-designed household air-conditioner or furnace leaves the home to cool or too warm - unless regulated by the feedback of thermostat. It is an outcome-based mindset.

| Conventional brakes in automobiles apply stopping action or friction against the rotating wheels as long as the brake pedal is pressed down by the driver. Serious accidents happen when the brakes lock and cause the vehicle to lose control. To avoid this undesired situation drivers are taught not to slam the brakes, rather apply them in pumping action while constantly monitoring the braking outcome. This open-loop design expects too much of the driver's braking skills and composure by ignoring the possibility of conditioned reflexes, not taking into account the human limits of information processing, and other complicating factors such as road condition, weather, and vehicle load. Anti-lock brakes (ABS) use electronic sensors to detect the locking of brakes and loss of traction under the wheels and immediately adjust the input, cutting off and applying the braking action in rapid succession until the optimal pressure is applied on the wheels. They can override the driver's input by taking into account other factors that the driver may not be able to quickly apply. In that sense, the outcome is maintained even in the presence of rogue input.

|

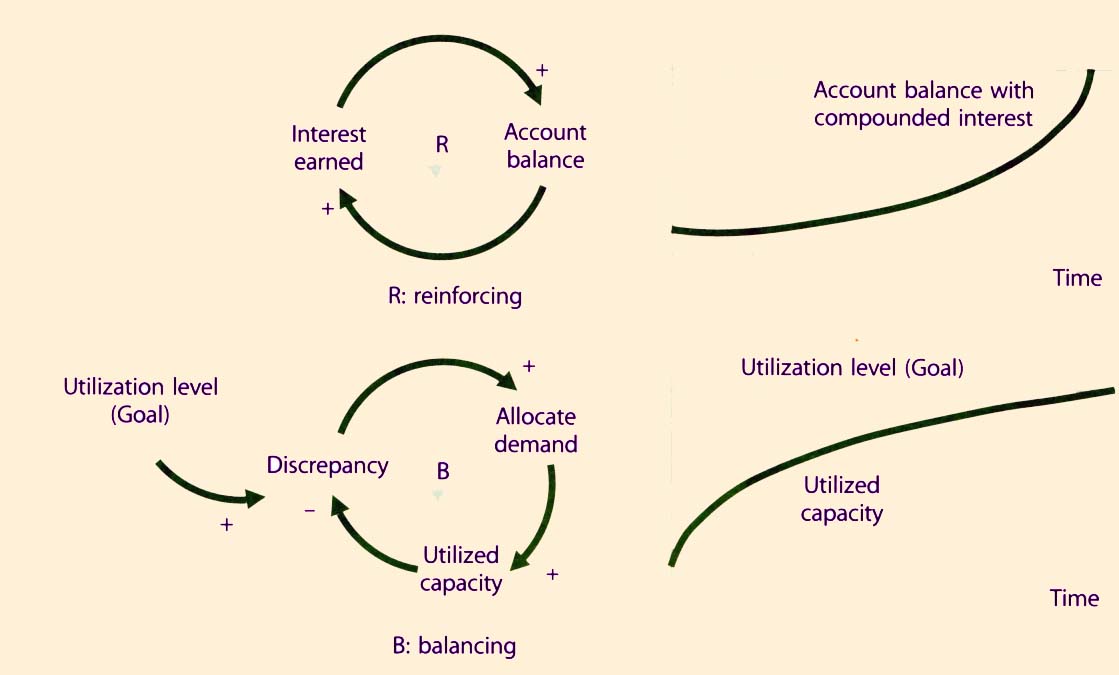

2.4.4.2 Feedback and Learning

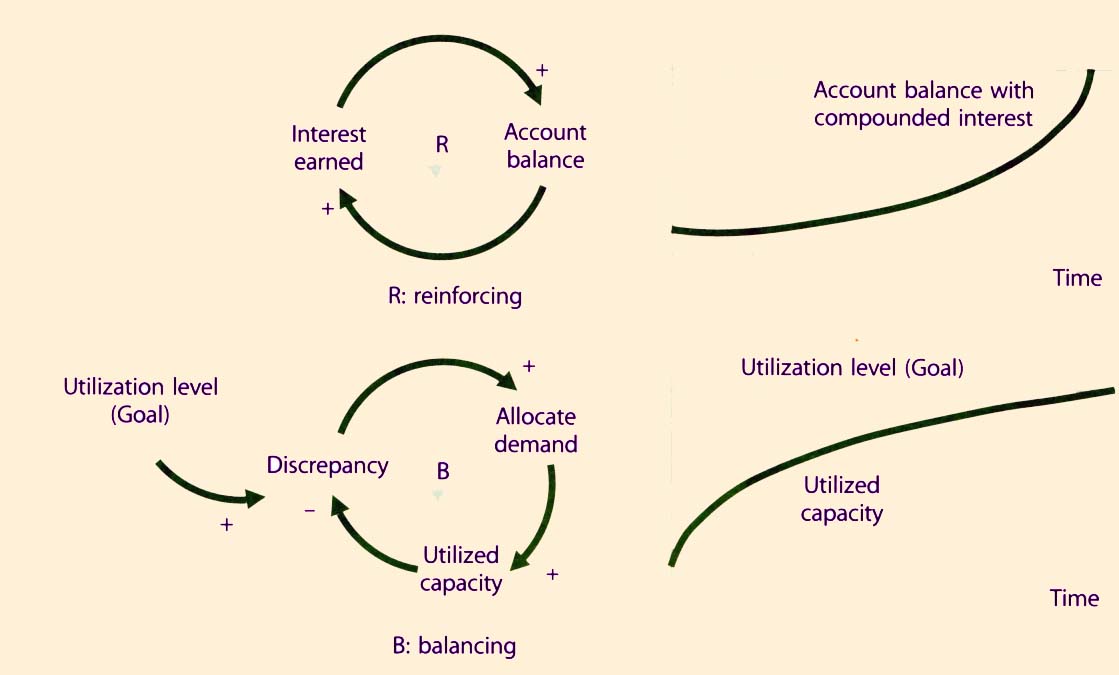

|

| Figure 2.9 Types of feedback |

|

Learning and growth are essential aspects of the way successful organizations function. Learning occurs from the presence of feedback as an input to a process in one cycle based on performance or outcome in the previous cycle. The feedback can be positive or self-reinforcing, leading to exponential growth or decline (Figure 2.9). It can be negative or self-correcting leading to balance or equilibrium. Goal-seeking behaviour is a widely observed pattern of control possible because of self-correcting feedback.

Functions, processes, and organizations can have more than one feedback loop of each type. The interaction of the feedback loops drives the behaviour of the process as it functions as a dynamic system. It is possible to visualize IT organizations as dynamic systems with functions and processes, with specialization and coordination, providing each other feedback towards the goal of meeting customer objectives. Interaction can be between processes, lifecycle phases, and functions. It is important to note that delays in negative feedback lead to oscillations or swings in the system due to intervening corrections. Improved measurement and reporting can reduce this destabilizing effect. The changes in output are not always linear or proportional to changes in input. This means that non-linearity is a widely observed characteristic of real world systems such as service organizations. Understanding these principles helps managers correctly identify the nature of challenges and opportunities by deivering patterns in performance of functions and processes. |

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

2.5 The Service Lifecycle

Case example 1: Telecommunication Services

Some time during the 1990s, a large internet service provider switched its internet service offerings from variable pricing to all-you-can-use fixed pricing. The strategic intent was to differentiate from competitor services through superior pricing plans. The service strategy worked exceedingly well - customers flocked to sign up. The outcomes, however, included large numbers of customers facing congestion or the inability to log on.

Why was there such a disconnection between the strategy and operations?R

|

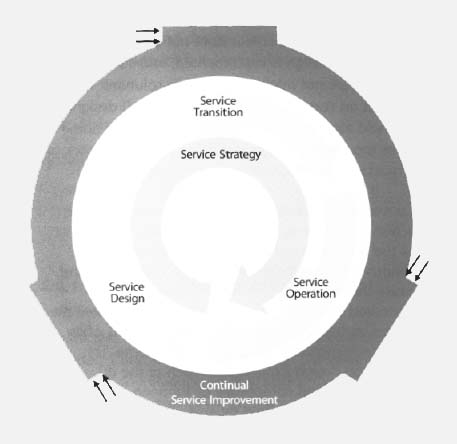

The Lifecycle

|

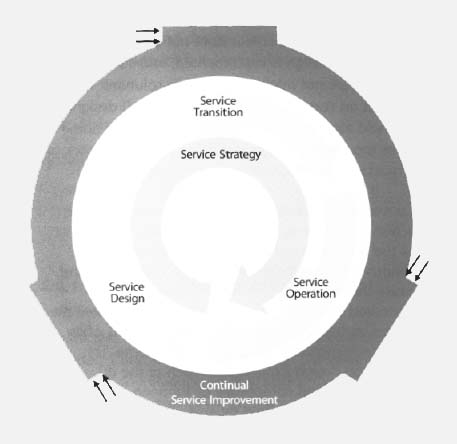

| Figure 2.10 The Service Lifecycle |

|

The architecture of the ITIL Core is based on a Service Lifecycle. Each volume of the core is represented in the Service Lifecycle (Figure 2.10). Service Design, Service Transition and Service Operation are progressive phases of the Lifecycle that represent change and transformation. Service Strategy represents policies and objectives. Continual Service Improvement represents learning and improvement.

Service Strategy (SS) is the axis around which the lifecycle rotates. Service Design (SD), Service Transition (ST), and Service Operation (SO) implement strategy. Continual Service Improvement (CSI) helps place and prioritize improvement programmes and projects based on strategic objectives. |

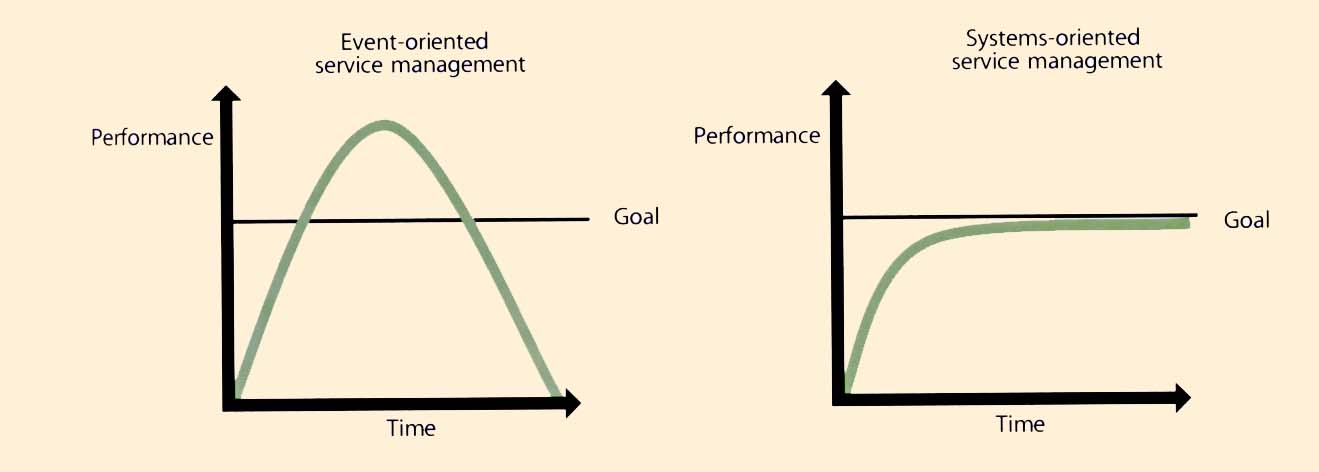

2.5.1 The Lifecycle And Systems Thinking

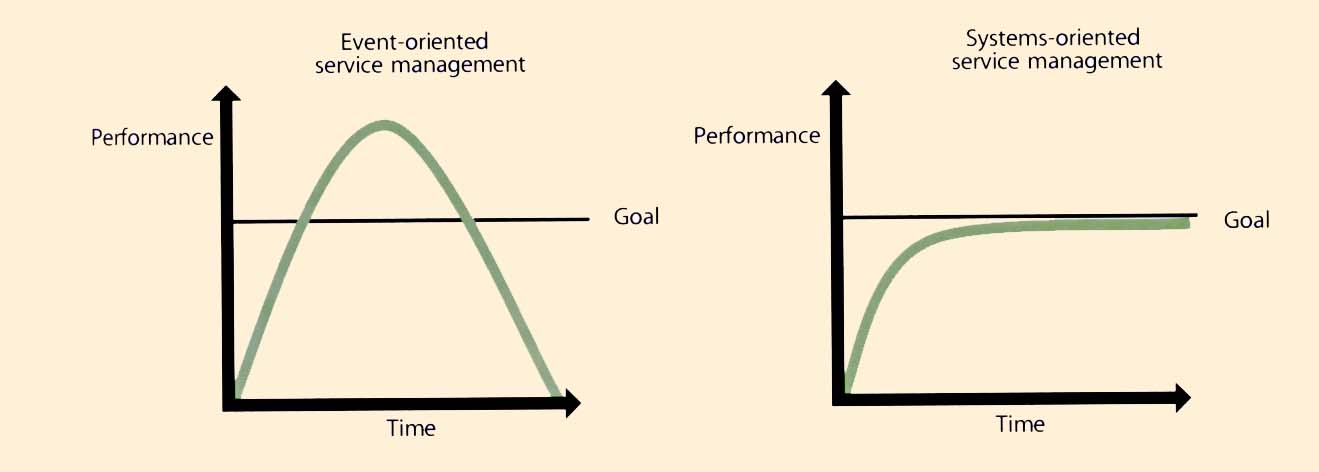

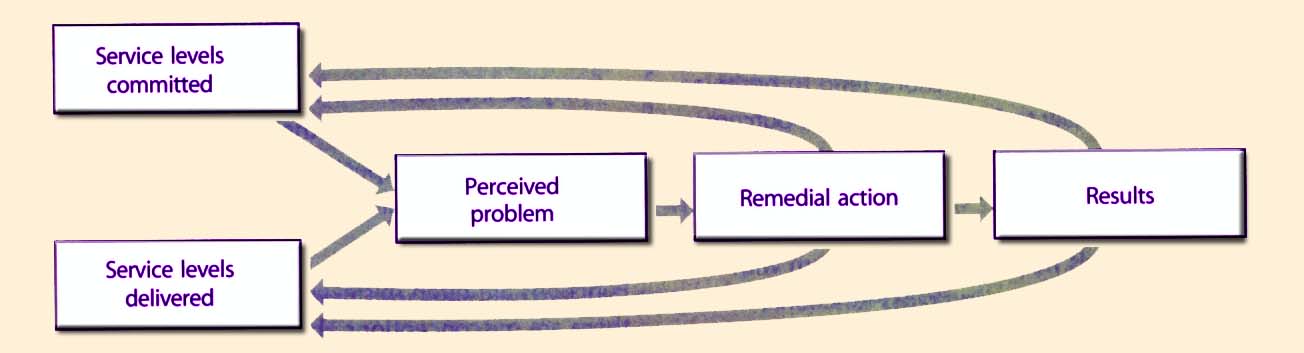

While feedback samples output to influence future action, structure is essential for organizing unrelated information. Without structure, our service management knowledge is merely a collection of observations, practices and conflicting goals. The structure of the Service Lifecycle is an organizing framework. Processes describe how things change, whereas structure describes how they are connected. Structure determines behaviour. Altering the structure of service management can be more effective than simply controlling discrete events (Figure 2.11). Without structure, it is difficult to learn from experience. It is difficult to use the past to educate for the future. We believe we can learn from experience but we never directly confront many of the most important consequences of our actions.

|

| Figure 2.11 Great leveerage for sustainable change lies in this structure |

|

The Service Lifecycle is a comprehensive approach to service management: seeking to understand its structure, the interconnections between all its components, and how changes in any area will affect the whole system and its constituent parts over time (Figure 2.12). It is an organizing framework designed for sustainable performance. A systems approach to service management ensures learning and improvement through a big-picture view of services and service management. It extends the management horizon and provides a sustainable long term approach (Figure 2.13).

|

|

Figure 2.12 Today's problem is often created by yesterday's solution

|

|

| Figure 2.13 Performance Over Time For Differing Service Management Structures |

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)

2.6 Functions And Processes Across The Lifecycle

2.6.1 Functions

Functions are units of organizations specialized to perform certain types of work and be responsible for specific outcomes. They are self-contained with capabilities and resources necessary for their performance and outcomes. Capabilities include work methods internal to the functions. Functions have their own body of knowledge, which accumulates from experience. They provide structure and stability to organizations.

Functions are a way of structuring organizations to implement the specialization principle. Functions typically define roles and the associated authority and responsibility for a specific performance and outcomes. Coordination between functions through shared processes is a common pattern in organization design. Functions tend to optimize their work methods locally to focus on assigned outcomes. Poor coordination between functions combined with an inward focus lead to functional silos that hinder alignment and feedback critical to the success of the organization as a whole. Process models help avoid this problem with functional hierarchies by improving cross-functional coordination and control. Well-defined processes can improve productivity within and across functions.

2.6.2 Processes

Processes that provide transformation towards a goal, and utilize feedback for self-reinforcing and self-corrective action, function as closed-loop systems (Figure 2.14). It is important to consider the entire process or how one process fits into another.

Process definitions describe actions, dependencies and sequence. Processes have the following characteristics:

- Processes are measurable - we are able to measure the process in a relevant manner. It is performance driven. Managers want to measure cost, quality and other variables while practitioners are concerned with duration and productivity.

- They have specific results - the reason a process exists is to deliver a specific result. This result must be individually identifiable and countable. While we can count changes, it is impossible to count how many Service Desks were completed. So change is a process and Service Desk is not: it is a function.

- Processes have customers - every process delivers its primary results to a customer or stakeholder. They may be internal or external to the organization but the process must meet their expectations.

- They respond to specific events - while a process may be ongoing or iterative, it should be traceable to a specific trigger.

Functions are often mistaken for processes. For example, there are misconceptions about Capacity Management being a service management process. First, Capacity Management is an organizational capability with specialized processes and work methods. Whether or not it is a function or a process depends entirely on organization design. It is a mistake to assume that Capacity Management can only be a process. It is possible to measure and control capacity and to determine

whether it is adequate for a given purpose. Assuming that it is always a process with discrete countable outcomes can be an error.

|

| Figure 2.15 Service management processes are applied across the Service Lifecycle |

Specialization and coordination are necessary in the lifecycle approach. Feedback and control between the functions and processes within and across the elements of the lifecycle make this possible (Figure 2.15). The dominant pattern in the lifecycle is the sequential progress starting from SS through SD-ST-SO and back to SS through CSI. That, however, is not the only pattern of action. Every element of the lifecycle provides points for feedback and control.

The combination of multiple perspectives allows greater flexibility and control across environments and situations. The lifecycle approach mimics the reality of most organizations where effective management requires the use of multiple control perspectives. Those responsible for the design, development and improvement of processes for service management can adopt a process-based control perspective. Those responsible for managing agreements, contracts, and services may be better served by a lifecycle-based control perspective with distinct phases. Both these control perspectives benefit from systems thinking. Each control perspective can reveal patterns that may not be apparent from the other.

![[To top of Page]](../../../images/up.gif)