|

| 4.1PLAN/SUPPORT | 4.2CHANGE | 4.3ASSET/CONFIG | 4.4RELEASE/DEPLOY | 4.5 VALIDATE/TEST | 4.6EVALUATE | 4.7KNOWLEDGE |

| 1Introduction | 2Serv. Mgmt. | 3Principles | 4Processes | 5Activities | 6Organization | 7Consideration | 8Implementation | 9Issues | AAppendeces |

|

| 4.1PLAN/SUPPORT | 4.2CHANGE | 4.3ASSET/CONFIG | 4.4RELEASE/DEPLOY | 4.5 VALIDATE/TEST | 4.6EVALUATE | 4.7KNOWLEDGE |

Changes should be managed to:

Such an approach will deliver direct benefit to the bottom line for the business by delivering early realization of benefits (or removal of risk), with a saving of money and time.

To make an appropriate response to all requests for change entails a considered approach to assessment of risk and business continuity, change impact, resource requirements, change authorization and especially to the realizable business benefit. This considered approach is essential to maintain the required balance between the need for change and the impact of the change.

This section provides information on the Change Management process and provides guidance that is scalable for:

The goals of Change Management are to:

|

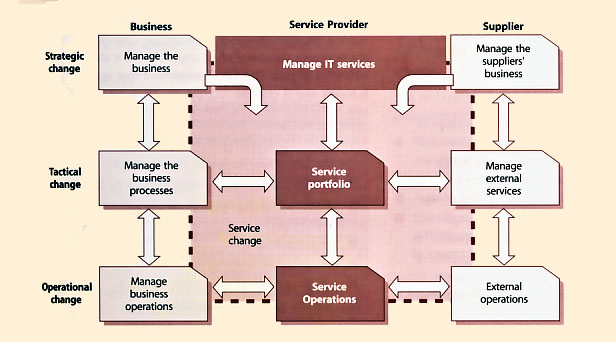

| Figure 4.1 Scope of change and release management for services |

Change can be defined in many ways. The definition of a service change is:

Service Change'The addition, modification or removal of authorized, planned or supported service or service component and its associated documentation.' |

The scope of Change Management covers changes to baselined service assets and configuration items across the whole service lifecycle.

Each organization should define the changes that lie outside the scope of their service change process. Typically these might include:

Figure 4.1 shows a typical scope for the service Change Management process for an IT department and how it interfaces with the business and suppliers at strategic, tactical and operational levels. It covers interfaces to internal and external service providers where there are shared assets and configuration items that need to be under Change Management. Service Change Management must interface with business Change Management (to the left in Figure 4.1), and with the supplier's Change Management (to the right in the figure). This may be an external supplier with a formal Change Management system, or with the project change mechanisms within an internal development project.

The Service Portfolio provides a clear definition of all current, planned and retired services. Understanding the Service Portfolio helps all parties involved in the Service Transition to understand the potential impact of the new or changed service on current services and other new or changed services.

Strategic changes are brought in via Service Strategy and the business relationship management processes. Change, to a service will be brought in via Service Design, Continual Service Improvement and the service level management process. Corrective change, resolving errors detected in services, will be initiated from Service Operations, and may route via support or external suppliers into a formal RFC.

Exclusions

This chapter does not cover strategic planning for business, transformation or organizational change although the interfaces to these processes do need to be managed. Guidance on organizational change is addressed in Chapter 5. Business transformation is the subject of many publications aimed at the general business manager.

Example of IT service initiated business changeIn the retail industry, bar-coding of goods coupled with bar-code readers at the check-out was initially introduced to deliver savings by removing the need to label every item, automating stock control, speeding customer throughput and reducing checkout staff. Suggestions from IT to the business resulted in making use of this facility to power innovative concepts such as Buy One Get One Free and capturing data on each individual's purchasing habits. |

The reliance on IT Services and underlying information technology is now so complex that considerable time can be spent on:

There are therefore considerable cost saving and efficiencies to be gained from well-structured and planned changes and releases.

As there is so much focus today on enterprise risk management, Change Management is a key process that comes under the scrutiny of auditors. The Institute of Internal Auditors, Global Technology Audit Guide, Change and Patch Management Controls: Critical for Organizational Success, provides guidance on assessing Change Management capability of an organization. It identifies risk indicators of poor Change Management that apply to business and IT change:

| 'By managing changes, you manage much of the potential risk that changes can introduce'

The top five risk indicators of poor Change Management are:

|

The following paragraph is extracted from the guide:

| What do all high-performing IT organizations have in common? They have a culture of Change Management that prevents and deters unauthorized change. They also 'trust but verify' by using independent detective controls to reconcile production changes with authorized changes, and by ruling out change first in the repair cycle during outages. Finally, they also have the lowest mean time to repair (MTTR). Auditors will appreciate (hat in these high-performing IT organizations, Change Management is not viewed as bureaucratic, but is instead the only safety net preventing them from becoming a low-performer. In other words, IT management owns the controls to achieve its own business objectives, efficiently and effectively. Achieving a change success rate over 70 percent is possible only with preventive and detective controls. |

|

Note: Mean Time to Restore Service (MTRS) should be used to avoid the ambiguity of Mean Time To Repair (MTTR). Although MTTR is a widely accepted industry term, in some definitions 'repair' includes only repair time but in others includes recovery time. The downtime in MTRS covers all the contributory factors that make the service, component or Cl unavailable. MTRS is a measure of how quickly and effectively a service, component or Cl can be restored to normal working after a failure and should be calculated using the following formula:

|

Pressure will be applied to reduce timescales and meet deadlines; to cut budgets and running costs; and to compromise testing. This must not be done without due diligence to governance and risk. The Service Transition management team will be called on from time to time to make a 'no go' decision and not implement a required change. There must be policies and standards defined which make it clear to the internal and external providers what must be done and what the consequence of nonadherence to policy will be.

Policies that support Change Management include:

The requirements and design for the Change Management processes include:

As much use as possible should be made of devolved authorization, both through the standard change procedure (see paragraph 4.2.4.4) and through the authorization of minor changes by Change Management staff. During the planning of different types of change requests, each must be defined with a unique naming convention, (see paragraph 4.3.5.3). Table 4.3 provides examples of different types of change request across the service lifecycle.

For different change types there are often specific procedures, e.g. for impact assessment and change authorization.

Changes that require specialized handling could be treated in this way, such as emergency changes that may have different authorization and may be documented retrospectively.

| Type of change with examples | Documented work procedures | SS | SD | ST | SO | SCI |

Request for Change to Service Portfolios

| Service Change Management | |||||

Request for Change to Service or service definition

| Project Change Management procedure | |||||

Project change proposal

| Project Change Management procedure | |||||

| User access request | User access procedure | |||||

Operational activity

| Local procedure (often pre-authorized - see paragraph 4.2.4.4) | |||||

| Table 4.3 Example of Types of Request by Service Lifecycle Stage | ||||||

The change process model includes:

These models are usually input to the Change Management support tools in use and the tools then automate the handling, management, reporting and escalation of the process.

Approval of each occurrence of a standard change will be granted by the delegated authority for that standard change, e.g. by the budget holding customer for installation of software from an approved list on a PC registered to their organizational unit or by the third party engineer for replacement of a faulty desktop printer.

The crucial elements of a standard change are that:

Once the approach to manage standard changes has been agreed, standard change processes and associated change workflows should be developed and communicated. A change model would normally be associated with each standard change to ensure consistency of approach.

Standard changes should be identified early on when building the Change Management process to promote efficiency. Otherwise, a Change Management implementation can create unnecessarily high levels of administration and resistance to the Change Management process.

All changes, including standard changes, will have details of the change recorded. For some standard changes this may be different in nature from normal change records.

Some standard changes to configuration items may be tracked on the asset or configuration item lifecycle, particularly where there is a comprehensive CMS that provides reports of changes, their current status, the related configuration items and the status of the related Cl versions. In these cases the Change and Configuration Management reporting is integrated and Change Management can have 'oversight' of all changes to service CIs and release CIs.

Some standard changes will be triggered by the request fulfilment process and be directly recorded and passed for action by the service desk.

Overall Change Management activities include:

Typical activities in managing individual changes are:

Throughout all the process activities listed above and described within this section, information is gathered, recorded in the CMS and reported.

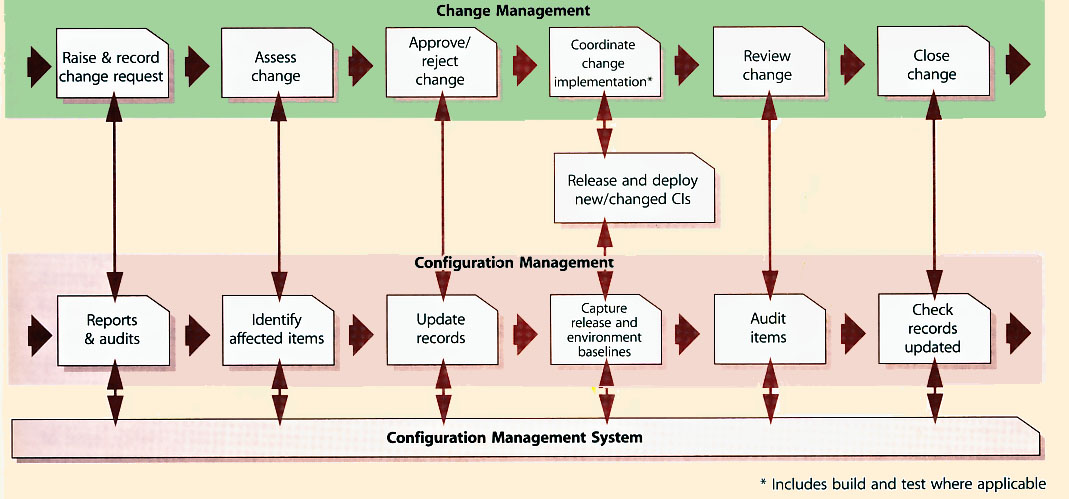

Figure 4.2 shows an example of a change to the service provider's services, applications or infrastructure. Examples of the states of the RFC are shown in italics. Change and configuration information is updated all the way through the activities. Figures 4.3 and 4.4 show the equivalent process flow for some examples of standard change process flows.

|

| Figure 4.2 Example process flow for a normal change |

|

|

For a major change with significant organizational and/or financial implications, a change proposal may be required, which will contain a full description of the change together with a business and financial justification for the proposed change. The change proposal will include signoff by appropriate levels of business management.

Table 4.4 shows an example of the information recorded for a change; the level of detail depends on the size and impact of the change. Some information is recorded when the document is initiated and some information may be updated as the change document progresses through its lifecycle. Some information is recorded directly on the Request for Change form and details of the change and actions may be recorded in other documents and referenced from the RFC, e.g. Business Case, impact assessment report.

| Attribute on the change record | RFC | Change proposal (if appropriate) | Related assets/CIs |

| Unique number | |||

| Trigger (e.g. to purchase order, problem report number, error records, business need, legislation) | |||

| Description | Summary | Full description | |

| Identity of item(s) to be changed - description of the desired change | Summary | Full description | Service (for enhancement) or Cl with errors (corrective changes) |

| Reason for change, e.g. Business Case | Summary | Full justification | |

| Effect of not implementing the change (business, technical, financial etc.) | |||

| Configuration items and baseline versions to be changed | Affected baseline/release | Details of CIs in baseline/release | |

| Contact and details of person proposing the change | |||

| Date and time that the change was proposed | |||

| Change category, e.g. minor, significant, major | Proposed | ||

| Predicted timeframe, resources, costs and quality of service | Summary/reference | Full | I |

| Change priority | Proposed | ||

| Risk assessment and risk management plan | Summary/reference | Full | |

| Back-out or remediation plan | Possibly | Full | |

| Impact assessment and evaluation - resources and capacity, cost, benefits | Provisional | Initial impact | |

| Would the change require consequential amendment of IT Service Continuity Management (ITSCM) plan, capacity plan, security plan, test plan? | Plans affected | ||

| Change decision body | |||

| Decision and recommendations accompanying the decision | |||

| Authorization signature (could be electronic) | |||

| Authorization date and time | |||

| Target baseline or release to incorporate change into | |||

| Target change plan(s) for change to be incorporated into | |||

| Scheduled implementation time (change window, release window or date and time) | |||

| Location/reference to release/implementation plan | |||

| Details of change implementer | |||

| Change implementation details (success/fail/remediation) | |||

| Actual implementation date and time | |||

| Review date(s) | |||

| Review results (including cross- reference to new RFC where necessary) | Summary | ||

| Closure Summary | Summary | ||

| Table 4.4 Example of contents of change documentation | |||

The change record holds the full history of the change, incorporating information from the RFC and subsequently recording agreed parameters such as priority and authorization, implementation and review information. There may be many different types of change records used to record different types of change. The documentation should be defined during the process design and planning stage.

Different types of change document will have different sets of attributes to be updated through the lifecycle. This may depend on various factors such as the change process model and change category but it is recommended that the attributes are standardized wherever possible to aid reporting.

Some systems use work orders to progress the change as this enables complete traceability of the change. For example work orders may be issued to individuals or teams to do an impact assessment or to complete work required for a change that is scheduled for a specific time or where the work is to be done quickly.

As an RFC proceeds through its lifecycle, the change document, related records (such as work orders) and related configuration items are updated in the CMS, so that there is visibility of its status. Estimates and actual resources, costs and outcome (success or failure) are recorded to enable management reporting.

Change logging

The procedures for logging and documenting RFCs should be decided. RFCs might be able to be submitted on paper forms, through e-mail or using a web-based interface, for example. Where a computer-based support tool is used, the tool may restrict the format.

All RFCs received should be logged and allocated an identification number (in chronological sequence). Where change requests are submitted in response to a trigger such as a resolution to a problem record (PR),

it is important that the reference number of the triggering document is retained to provide traceability. It is recommended that the logging of RFCs is done by means of an integrated Service Management tool, capable of storing both the data on all assets and CIs and also, importantly, the relationships between them. This will greatly assist when assessing the likely impact of a change to one component of the system on all other components. All actions should be recorded, as they are carried out, within the Change Management log. If this is not possible for any reason, then they should be manually recorded for inclusion at the next possible opportunity.

Procedures will specify the levels of access and who has access to the logging system. While any authorized personnel may create, or add reports of progress to, an RFC (though the support tool should keep Change Management aware of such actions) only Change Management staff will have permission to close an RFC.

These should be returned to the initiator, together with brief details of the reason for the rejection, and the log should record this fact. A right of appeal against rejection should exist, via normal management channels, and should be incorporated within the procedures.

The seven Rs of Change ManagementThe following questions must be answered for all changes. Without this information, the impact assessment cannot be completed, and the balance of risk and benefit to the live service will not be understood. This could result in the change not delivering all the possible or expected business benefits or even of it having a detrimental, unexpected effect on the live service.

|

Many organizations develop specific impact assessment forms to prompt the impact assessors about specific types of change. This can help with the learning process, particularly for new services or when implementing a formal impact assessment step for the first time.

Responsibility for evaluating major change should be defined. It is not a best-practice issue because organizations are so diverse in size, structure and complexity that there is not a universal solution appropriate to all organizations. It is, however, recommended that major change is discussed at the outset with all stakeholders in order to arrive at sensible boundaries of responsibility and to improve communications.

Although Change Management is responsible for ensuring that changes are assessed and, if authorized, subsequently developed, tested, implemented and reviewed, clearly final responsibility for the IT service - including changes to it - will rest with the service manager and the service owner. They control the funding available and will have been involved in the change process through direct or delegated membership of the CAB.

When conducting the impact and resource assessment for RFCs referred to them, Change Management, CAB, ECAB or any others (nominated by Change Management or CAB members) who are involved in this process should consider relevant items, including:

No change is without riskSimple changes may seem innocuous but can cause damage out of all apparent proportion to their complexity. There have been several examples in recent years of high profile and expensive business impact caused by the inclusion, exclusion or misplacing of a '.' in software code. |

Change impact | Change impact/risk categorization matrix | |

| High impact | High impact | |

| Low probability | High probability | |

| Risk category: 2 | Risk category: 1 | |

| Low impact | Low impact | |

| Low probability | High probability | |

| Risk category: 4 | Risk category: 3 | |

| Probability | ||

| Table 4.5 Example of a change impact and risk | ||

It is best practice to use a risk-based assessment during the impact assessment of a change or set of changes. For example the risk for:

The focus should be on identifying the factors that may disrupt the business, impede the delivery of service warranties or impact corporate objectives and policies. The same disciplines used for corporate risk management or in project management can be adopted and adapted.

Risk Categorization

The issue of risk to the business of any change must be considered prior to the authorisation of any change. Many organizations use a simple matrix like the one shown in Table 4.5 to categorize risk, and from this the level of change assessment and authorization required.

The relevant risk is the risk to the business service and changes require thorough assessment, wide communication, and appropriate authorization by the person or persons accountable for that business service. Assessing risk from the business perspective can produce a correct course of action very different from that which would have been chosen from an IT perspective, especially within high-risk industries.

High-Risk IndustryIn one volatile and competitive business environment, the mobile telephone supply business, customers asked IT if they were now able to implement a muchneeded change to the business software. The reply was that it could not go forward to the next change window because there was still a 30% risk of failure. Business reaction was to insist on implementation, for in their eyes a 70% chance of success, and the concomitant business advantage, was without any hesitation the right and smart move. Very few of their business initiatives had that high a chance of success.The point is that the risk and gamble of the business environment (selling mobile telephones) had not been understood within IT, and inappropriate (i.e. IT) rules had been applied. The dominant risk is the business one and that should have been sought, established, understood and applied by the service provider. Sensibly, of course, this might well be accompanied by documentation of the risk-based decision but nonetheless the need remains to understand the business perspective and act accordingly. |

Evaluation Of Change

Based on the impact and risk assessments, and the

potential benefits of the change, each of the assessors should evaluate the information and indicate whether they support approval of the change. All members of the change authority should evaluate the change based on

pact, urgency, risk, benefits and costs. Each will indicate whether they support approval and be prepared to argue their case for any alterations that they see as necessary.

Allocation of priorities

Prioritization is used to establish the order in which changes put forward should be considered.

Every RFC will include the originator's assessment of the impact and urgency of the change.

The priority of a change is derived from the agreed impact and urgency. Initial impact and urgency will be suggested

by the change initiator but may well be modified in the change authorization process. Risk assessment is of crucial importance at this stage. The CAB will need information on business consequences in order to assess effectively the risk of implementing or rejecting the change.

Impact is based on the beneficial change to the business that will follow from a successful implementation of the change, or on the degree of damage and cost to the business due to the error that the change will correct. The impact may not be expressed in absolute terms but may depend on the probability of an event or circumstance; for example a service may be acceptable at normal throughput levels, but may deteriorate at high usage, which may be triggered by unpredictable external items.

The urgency of the change is based on how long the implementation can afford to be delayed.

Table 4.6 gives examples of change priorities for corrective changes (fixing identified errors that are hurting the business) and for enhancements (that will deliver additional benefits). Other types of change exist, e.g. to enable continuation of existing benefit, but these two are used to illustrate the concept.

| Priority | Corrective change | Enhancement change |

| Immediate

Treat as emergency change | Putting life at risk Causing significant loss of revenue or the ability to deliver important public services. Immediate action required | Not appropriate for enhancement changes |

| High To be given highest priority for change building, testing and implementation resources | Severely affecting some key users, or impacting on a large number of users | Meets legislative requirements Responds to short term market opportunities or public requirements Supports new business initiatives that will increase company market position |

| Medium | No severe impact, but rectification cannot be deferred until the next scheduled release or upgrade | Maintains business viability Supports planned business initiatives |

| Low | A change is justified and necessary, but can wait until the next scheduled release or upgrade | Improvements in usability of a service Adds new facilities |

| Table 4.6 Change priority examples | ||

Change planning and scheduling

Careful planning of changes will ensure that there is no ambiguity about what tasks are included in the Change Management process, what tasks are included in other

processes and how processes interface to any suppliers or projects that are providing a change or release.

Many changes may be grouped into one release and may be designed, tested and released together if the amount of changes involved can be handled by the business, the service provider and its customers. However, if many independent changes are grouped into a release then this may create unnecessary dependencies that are difficult to manage. If not enough changes are grouped into a release then the overhead of managing more releases can be time consuming and waste resources (see paragraph 4.4.5.1 on release and deployment planning).

It is recommended very strongly that Change Management schedule changes to meet business rather than IT needs, e.g. avoiding critical business periods.

Pre-agreed and established change and release windows help an organization improve the planning and throughput of changes and releases. For example a release window in a maintenance period of one hour each week may be sufficient to install minor releases only. Major releases may need to be scheduled with the business and stakeholders at a pre-determined time. This approach is particularly relevant in high change environments where a release is a bottleneck or in high availability services where access to the live systems to implement releases is restricted. In many cases, the change or release may need to be adjusted 'on the fly', and so efficient use of release windows will require:

Wherever possible, Change Management should schedule authorized changes into target release or deployment packages and recommend the allocation of resources accordingly.

Change Management coordinates the production and distribution of a change schedule (CS) and projected service outage (PSO). The SC contains details of all the changes authorized for implementation and their proposed implementation dates. The PSO contains details of changes to agreed SLAs and service availability because of the currently planned SC in addition to planned downtime from other causes such as planned maintenance and data backup. These documents are agreed with the relevant customers within the business, with service level management, with the service desk and with availability management. Once agreed, the service desk should communicate any planned additional downtime to the user community at large, using the most effective methods available.

The latest versions of these documents will be available to stakeholders within the organization, preferably contained within a commonly available internet or intranet server. This can usefully be reinforced with a proactive awareness programme where specific impact can be detected.

Assessing remediation

It is important to develop a remediation plan to address a failing change or release long before implementation. Very often, remediation is the last thing to be considered; risks may be assessed, mitigation plans cast in stone. How to get back to the original start point is often ignored or considered only when regression is the last remaining option.

|

| Figure 4.5 Example of a change authorization model |

Formal authorization is obtained for each change from a change authority that may be a role, person or a group of people. The levels of authorization for a particular type of change should be judged by the type, size or risk of the change, e.g. changes in a large enterprise that affect several distributed sites may need to be authorized by a higher-level change authority such as a global CAB or the Board of Directors.

The culture of the organization dictates, to a large extent, the manner in which changes are authorized. Hierarchical structures may well impose many levels of change authorization, while flatter structures may allow a more streamlined approach.

A degree of delegated authority may well exist within an authorization level, e.g. delegating authority to a change manager according to pre-set parameters relating to:

An example of a change authorization hierarchy is shown in Figure 4.5.

If change assessment at levels 2, 3, or 4 detects higher levels of risk, the authorization request is escalated to the appropriate higher level for the assessed level of risk. The use of delegated authority from higher levels to local levels must be accompanied by trust in the judgement, access to the appropriate information and supported by management. The level at which change is authorized should rest where accountability for accepting risk and remediation exist.

Should disputes arise over change authorization or rejection, there should be a right of appeal to the higher level.

Change Management has responsibility for ensuring that changes are implemented as scheduled. This is largely a coordination role as the actual implementation will be the responsibility of others (e.g. hardware technical specialists will implement hardware changes).

Remediation procedures should be prepared and documented in advance, for each authorized change, so that if errors occur during or after implementation, these procedures can be quickly activated with minimum impact on service quality. Authority and responsibility for invoking remediation is specifically mentioned in change documentation.

Change Management has an oversight role to ensure that all changes that can be are thoroughly tested. In all cases involving changes that have not been fully tested, special care needs to be taken during implementation. Testing may continue in parallel with early live usage of a service - looking at unusual, unexpected or future situations so that further correcting action can be taken before any detected errors become apparent in live operation.

The implementation of such changes should be scheduled when the least impact on live services is likely. Support staff should be on hand to deal quickly with any incidents that might arise.

A review should also include any incidents arising as a result of the change (if they are known at this stage). If the change is part of a service managed by an external provider, details of any contractual service targets will be required (e.g. no priority 1 incidents during first week after implementation). A change review (e.g. post-implementation review, PIR) should be carried out to confirm that the change has met its objectives, that the initiator and stakeholders are happy with the results; and that there have been no unexpected side-effects. Lessons learned should be fed back into future changes. Small organizations may opt to use spot checking of changes rather than large-scale PIR; in larger organizations, sampling will have a value when there are many similar changes taking place.

There is a significantly different approach and profile between:

Change Management must review new or changed services after a predefined period has elapsed. This process will involve CAB members, since change reviews are a standard CAB agenda item. The purpose of such reviews is to establish that:

Further details of performing a formal evaluation are provided in Section 4.6. Any problems and discrepancies should be fed back to CAB members (where they have been consulted or where a committee was convened), impact assessors, product authorities and release authorities, so as to improve the processes for the future.

Where a change has not achieved its objectives, Change Management (or the CAB) should decide what follow-up action is required, which could involve raising a revised RFC. If the review is satisfactory or the original change is abandoned (e.g. the circumstances that required the change are no longer current and the requirement disappears) the RFC should be formally closed in the logging system.

4.2.6.8 Change Advisory Board

The Change Advisory Board (CAB) is a body that exists to support the authorization of changes and to assist Change Management in the assessment and prioritization of changes. As and when a CAB is convened, members should be chosen who are capable of ensuring that all changes within the scope of the CAB are adequately assessed from both a business and a technical viewpoint.

The CAB may be asked to consider and recommend the adoption or rejection of changes appropriate for higherlevel authorization and then recommendations will be submitted to the appropriate change authority.

To achieve this, the CAB needs to include people with a clear understanding across the whole range of stakeholder needs. The change manager will normally chair the CAB, and potential members include:

It is important to emphasize that the CAB:

When the need for emergency change arises, i.e. there may not be time to convene the full CAB, it is necessary to identify a smaller organization with authority to make emergency decisions. This body is the Emergency Change Advisory Board (ECAB). Change procedures should specify how the composition of the CAB and ECAB will be determined in each instance, based on the criteria listed above and any other criteria that may be appropriate to the business. This is intended to ensure that the composition of the CAB will be flexible, in order to represent business interests properly when major changes are proposed. It will also ensure that the composition of the ECAB will provide the ability, both from a business perspective and from a technical standpoint, to make appropriate decisions in any conceivable eventuality.

A practical tip worth bearing in mind is that the CAB should have stated and agreed evaluation criteria. This will assist in the change assessment activities, acting as a template or framework by which members can assess each change.

CAB meetings

Many organizations are running CABs electronically without frequent face-to-face meetings. There are benefits and problems from such an approach. Much of the assessment and referral activities can be handled electronically via support tools or e-mail. In complex, highrisk or high-impact cases, formal CAB meetings may be necessary.

Handling electronically is more convenient time-wise for CAB members but is also highly inefficient when questions or concerns are raised such that many communications go back and forth. A face-to-face meeting is generally more efficient, but poses scheduling and time conflicts among CAB members as well as significant travel and staff costs for widely dispersed organizations.

Practical experience shows that regular meetings combined with electronic automation is a viable approach for many organizations, and that it can be beneficial to schedule a regular meeting, or when major projects are due to deliver releases. The meetings can then be used to provide a formal review and sign-off of authorized changes, a review of outstanding changes, and, of course, to discuss any impending major changes. Where meetings are appropriate, they should have a standard agenda.

A standard CAB agenda should include:

CAB meetings represent a potentially large overhead on the time of members. Therefore all RFCs, together with the SC and PSO, should be circulated in advance, and flexibility allowed to CAB members on whether to attend in person, to send a deputy, or to send any comments. Relevant papers should be circulated in advance to allow CAB members (and others who are required by Change Management or CAB members) to conduct impact and resource assessments.

In some circumstances it will be desirable to table RFCs at one CAB meeting for more detailed explanation or clarification before CAB members take the papers away for consideration, in time for a later meeting. A 'walkthrough' of major changes may be included at a CAB meeting before formal submission of the RFC.

CAB members should come to meetings prepared and empowered to express views and make decisions on behalf of the area they represent in respect of the submitted RFCs, based on prior assessment of the RFCs. The CAB should be informed of any emergency changes or changes that have been implemented as a workaround to incidents and should be given the opportunity to recommend follow-up action to them.

Note that the CAB is an advisory body only. If the CAB cannot agree to a recommendation, the final decision on whether to authorize changes, and commit to the expense involved, is the responsibility of management (normally the director of IT or the services director, service manager or change manager as their delegated representative). The Change Management authorization plan should specifically name the person(s) authorized to sign off RFCs.

The number of emergency changes proposed should be kept to an absolute minimum, because they are generally more disruptive and prone to failure. All changes likely to be required should, in general, be foreseen and planned, bearing in mind the availability of resources to build and test the changes. Nevertheless, occasions will occur when emergency changes are essential and so procedures should be devised to deal with them quickly, without sacrificing normal management controls.

Emergency change is reserved for changes intended to repair an error in an IT service that is negatively impacting the business to a high degree. Changes intended to introduce immediately required business improvements are handled as normal changes, assessed as having the highest urgency.

Emergency Change Authorization

Defined authorization levels will exist for an emergency change, and the levels of delegated authority must be clearly documented and understood. In an emergency situation it may not be possible to convene a full CAB meeting. Where CAB approval is required, this will be provided by the Emergency CAB (ECAB).

Not all emergency changes will require the ECAB involvement; many may be predictable both in occurrence and resolution and well understood changes available, with authority delegated, e.g. to Operations teams who will action, document and report on the emergency change.

Emergency Change Building, Testing And Implementation

Authorized changes are allocated to the relevant technical group for building. Where timescales demand it, Change Management, in collaboration with the appropriate technical manager, ensures that sufficient staff and resources (machine time etc.) are available to do this work. Procedures and agreements - approved and supported by management - must be in place to allow for this. Remediation must also be addressed.

As much testing of the emergency change as is possible should be carried out. Completely untested changes should not be implemented if at all avoidable. Clearly, if a change goes wrong, the cost is usually greater than that of adequate testing. Consideration should be given to how much it would cost to test all changes fully against the cost of the change failing factored by the anticipated likelihood of its failure.

This means that the less a change is considered likely to fail, the more reasonable it may be to reduce the degree of testing in an emergency. (Remember that there is still merit in testing even after a change has gone live.) When only limited testing is possible - and presuming that parallel development of more robust versions continues alongside the emergency change - then testing should be targeted towards:

The business should be made aware of associated risks and be responsible for ultimately accepting or rejecting the change based on the information presented.

Change Management will give as much advance warning as possible to the service desk and other stakeholders, and arrange for adequate technical presence to be available, to support Service Operations.

If a Change, once implemented, fails to rectify the urgent outstanding error, there may need to be iterative attempts at fixes. Change Management should take responsibility at this point to ensure that business needs remain the primary concern and that each iteration is controlled in the manner described in this section. Change Management should ensure abortive changes are swiftly backed out.

If too many attempts at an emergency change are abortive, the following questions should be asked:

In such circumstances, it may be better to provide a partial service, with some user facilities withdrawn, in order to allow the change to be thoroughly tested or to suspend the service temporarily and then implement the change.

Emergency Change Documentation

It may not be possible to update all Change Management records at the time that urgent actions are being completed (e.g. during overnight or weekend working). It is, however, essential that temporary records are made

during such periods, and that all records are completed retrospectively, at the earliest possible opportunity.

Incident control staff, computer operations and network management staff may have delegated authority to circumvent certain types of incident (e.g. hardware failure) without prior authorization by Change Management. Such circumventions should be limited to actions that do not change the specification of service assets and that do not attempt to correct software errors. The preferred methods for circumventing incidents caused by software errors should be to revert to the previous trusted state or version, as relevant, rather than attempting an unplanned and potentially dangerous change. Change approval is still a prerequisite.

Effectively, the emergency change procedure will follow the normal change procedure except that:

Typical examples of types of change that trigger the Change Management process are described below.

Strategic Changes

Service strategies require changes to be implemented to achieve specific objectives while minimizing costs and risks. There are no cost-free and risk-free strategic plans or initiatives. There are always costs and risks associated with decisions such as introducing new services, entering new market spaces, and serving new customers. The following are examples of programmes and initiatives that implement strategic changes:

Change To One Or More Services

Changes to the planned services (in the Service Portfolio) and changes to the services in the service catalogue will trigger the Change Management process. These include changes to:

Service Operations staff will also implement corrective and preventative changes, via the standard change procedure, that should be managed through Change Management, e.g. server re-boot, which may impact a shared service.

Changes To Deliver Continual Improvement

When CSI determines that an improvement to a Service is warranted, an RFC should be submitted to Change

Management. Changes such as changes to processes can have an effect on service provision and may also affect other CSI initiatives.

Some strategy and service changes will be initiated by CSI.

Integration With Business Change Processes

Where appropriate, the Change Management should be involved with business programme and business project management teams to ensure that change issues, aims, impacts and developments are exchanged and cascaded throughout the organization where applicable. This means that changes to any business or project deliverables that do not impact services or service components may be subject to business or project Change Management procedures rather than the IT service Change Management procedures. However, care must be taken to ensure that changes to service configuration baselines and releases do follow the Change Management process. The Change Management team will, however, be expected to liaise closely with projects to ensure smooth implementation and consistency within the changing management environments.

Programme And Project Management

Programme and project management must work in partnership to align all the processes and people involved in service change initiatives. The closer they are aligned, the higher the probability that the change effort will be moved forward for as long as it takes to complete. Change Management representatives may attend relevant Project Board meetings.

Sourcing and partnering arrangements should clearly define the level of autonomy a partner may have in effecting change within their service domain without reference to the overall service provider. A key component is how deeply change processes and tools are embedded into the supplier organization or vice versa and where the release veto takes place. If the supplier has responsibility for the availability of the operational service, conflicts can arise.

Sourcing And Partnering

Sourcing and partnering include internal and external vendors and suppliers who are providing a new or existing service to the organization. Effective Change Management practices and principles must be put into place to manage these relationships effectively to ensure smooth delivery of service. Effort also should be put into finding out how well the partners themselves manage change and choose partner and sourcing relationships accordingly.

It is important to ensure that service providers (outsourced or in house) provide the Change Management function and processes that match the needs of the business and customers. Some organizations in outsourcing situations refer RFCs to their suppliers for estimates prior to approval of changes. For further information, refer to the ITIL Service Design publication and guidance on supplier management.

Asset and Configuration Management

|

| Figure 4.6 Request for Change workflow and key interfaces to Configuration Management |

The Configuration Management System provides reliable, quick and easy access to accurate configuration information to enable stakeholders and staff to assess the impact of proposed changes and to track changes work flow. This information enables the correct asset and service component versions to be released to the appropriate party or into the correct environment. As changes are implemented, the Configuration Management information is updated.

The CMS may also identify related Cl/assets that will be affected by the change, but not included in the original request, or in fact similar Cl/assets that would benefit from similar change. An overview of how the change and Configuration Management processes work together for an individual change is shown in Figure 4.6.

Problem Management

Problem Management is another key process as changes are often required to implement workarounds and to fix known errors. Problem Management is one of the major sources of RFCs and also often a major contributor to CAB discussion.

IT Service Continuity

IT Service Continuity has many procedures and plans should be updated via Change Management to ensure that they are accurate, up to date and that stakeholders are aware of changes.

Security Management

Security Management interfaces with Change Management since changes required by security will go via the Change Management process and security will be a key contributor to CAB discussion on many services. Every significant change will be assessed for its potential impact on the security plan.

Capacity and Demand Management

Capacity and Demand Management is a critical aspect of Change Management. Poorly managed demand is a source of costs and risk for service providers because there is always a level of uncertainty associated with the demand for services. Capacity Management has an important role in assessing proposed changes - not only the individual changes but the total impact of changes on service capacity. Changes arising from Capacity Management, including those set out in the capacity plan, will be initiated as RFCs through the change process.

Measures taken should be linked to business goals wherever practical - and to cost, service availability, and reliability. Any predictions should be compared with actual measurements.

The key performance indicators for Change Management are:

Naturally there is other management information required around change and statistics to be gathered and analysed to ensure efficient and effective process, but for organizations with a 'dashboard' reporting approach, these are good metrics to use.

Meaningful measurements are those from which management can make timely and accurate actionable decisions. For example, reporting on the number of changes is meaningless. Reporting on the ratio of changes implemented versus RFCs received provides an efficiency rating. If this rating is low, management can easily see that changes are not being processed in an efficient or effective manner and then take timely action to correct the deficiencies causing this.

Output Measures

Workloads

Process Measures

Supporting Material |

|

|